In Focus

Violent Extremist Offenders Rehabilitation and Reintegration in prison: a focus on the challenges and way forward in Mali

By Elise Vermeersch and Elena Dal Santo

Introduction

In his remarks to the High-level Meeting on Mali and the Sahel held on the margins of the General Debate of the 74th session of the UN General Assembly, the Secretary General António Guterres acknowledged the increasing threat posed by the rise of violence in the Sahel and its spreading towards the Gulf of Guinea. He also warned about terrorist groups exploiting local conflicts and acting as defenders of communities to enhance their popularity and local support. As a matter of fact, countries in the Sahel region have been experiencing a significant increase in the level of violence, resulting in severe consequences for the population. According to Mohamed Ibn Chambas, UN Special Representative and Head of the United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), the casualties caused by terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, have increased five-fold since 2016. The fragile circumstances and the deteriorating security situation have also pushed many people to flee their homes, with more than one million refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) sheltered in the central Sahel.

As the countries in the Sahel region face increasing security threats resulting from terrorism, organized crime and inter-community tensions, the pressure on the prison systems escalates. Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Mali and Mauritania present the highest prison overcrowding rates in the world, ranging from 120% to 232%. Within this framework, a specific threat is represented by the risks of radicalization and/or recruitment taking place in the prison settings in light of the increasing number of suspected violent extremists within both the judicial and correctional systems.

Prisons, with their peculiar characteristics, certainly represent an environment where inmates are more vulnerable as a result of the restrictions of freedom, the loss of means of subsistence, personal effects and housing, the loss of important personal relationships and the deterioration of social and family ties. All these factors may increase the chances of inmates becoming more easily attracted by the advantages of taking part in a radical group while in detention. On the other hand, prisons can play a multi-faceted role in identifying, assessing and countering radicalization and recruitment. Such a unique environment represents an opportunity for the implementation of tailored rehabilitation activities, including targeted rehabilitative measures, capacity-building initiatives and awareness raising opportunities. Under certain circumstances and within the framework of tailored initiatives, incarceration may thus reduce the risk and instead mark the beginning of a disengagement process. In this regard, the design and development of effective rehabilitation and reintegration programs can prevent further radicalization and help deradicalize inmates convicted of terrorism-related offences.

The current article is aimed at assessing the main challenges and opportunities for the development and implementation of targeted rehabilitation and reintegration (R&R) measures for the violent extremist offender (VEO) population in detention in Mali. The first part will provide an overview of the Malian prison system, while the second will focus on the trajectories of violence of the VEO population in Mali. The third section will elaborate on the main challenges faced by the prison administration in the management of suspected/convicted violent extremist offenders, including the development of rehabilitation and reintegration measures. Finally, the conclusion will portray some alternatives in terms of future tailored R&R initiatives for the VEOs population in Mali.

Methodology

In the context of a series of initiatives aimed at countering violent extremism in prisons and fostering community resilience against violent extremism in Mali, the United Nationals Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), together with the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), have developed and implemented a set of activities over the past four years both within as well as outside the prison settings. This publication is built on this experience and is based on the analysis of existing literature on the region and on the radicalisation process, combined with data gathered during field missions organized by UNICRI and ICCT. Primary data were collected through fieldnotes, as well as unstructured interviews with local, national and international actors, and thirty semi-structured interviews with inmates accused of/ convicted for terrorism-related offences. The semi-structured interviews 1were conducted between 2016 and 2019 in Bamako’s central prison, to enhance the understanding of the detainees’ background and their reasons for engagement with terrorist groups. Finally, supplementary data were gathered on 22 additional VEOs in Bamako Prison in 2019.

1. Overview of the prison system in Mali

Within the Ministry of Justice, the Malian prison administration is directed and managed by the Direction National de l'Administration Pénitentiaire et de l’Education Surveillée (DNAPES), which serves the twofold purpose of custody and reintegration of detainees. The country counts 59 detention centers, including some agricultural and specialized establishments, of which 14 have been destroyed by the conflict in 2013. A new and capacious prison is under construction in the town of Kenieroba, located in the district of Koulikoro, approximately 75 kilometres in the South West of Bamako.

The increased number of arrests due to the criminal activities occurring in the country as well as the impact of the conflict on the detention facilities have been worsening the already critical levels of prison overpopulation. At the end of 2018, the overall prison population exceeded 6,250 inmates. Compared to the official capacity of approximately 3,000 inmates as of 2009, the actual occupancy rate would translate to a general congestion rate of roughly 175%. The number of pre-trial detention cases constitutes a considerable burden for the Malian prison system, with an estimated representation of 60 to 90% of the prison population2 according to various sources. The main prison in Bamako, the Maison Centrale d’Arrêt, has an official capacity of 400 inmates, but, at the end of 2019, it was housing 2,400 people, leading to a congestion rate of 615%. The issue of overpopulation is supposed to be addressed with the new prison of Kenieroba which should have a capacity of 2,500 inmates. At the end of 2019, a group of approximately 440 low-risk offenders were transferred to Kenieroba prison on a trial-basis.

Prison’s actors

Under the authority of the DNAPES, each detention centre is headed by a prison director, or régisseur, in charge of the overall prison management, including both of inmates and staff. Prison personnel is mainly comprised of guards and security officers, managing the prison population on a daily basis and maintaining operational security within the facility. In addition, administrative staff usually composed of fewer individuals are responsible for keeping the general prison administration up to date, registering new inmates and visitors and managing the prison archives. Depending on the available resources, some prisons also employ social workers to focus on prison welfare, as well as rehabilitation and reintegration interventions. In terms of health care, some facilities can count on a doctor or nurse(s) working in the prison, while in other detention centres doctors/nurses visit at regular intervals.

The prison environment also entails connections and links with several external actors. In particular, religious leaders generally visit once a week, for example to conduct the Friday sermon for Muslims and/or to lead Sunday prayer services with Christian inmates. In addition, various international organisations, civil society, or non-governmental organisations (such as MINUSMA3, ICRC4, Prisonnier Sans Frontière, UNICRI, ICCT and Think Peace) support the overall prison management by providing basic services (such as kitchen machinery, healthcare material), education materials or equipment for vocational occupations (such as cloth-making, woodwork, or agriculture); delivering capacity-building activities (e.g. UNICRI and ICCT provided several trainings for security officers, psychologists and religious leaders working in prison to promote the rehabilitation of VEOs in prison); or by conducting research and analysis on needs, gaps and priorities linked to the prison environment. Finally, family members, who generally visit prisoners on pre-approved days and times, may also play a central role in basic services such as provision of additional food as well as relational and emotional support.

Intake process

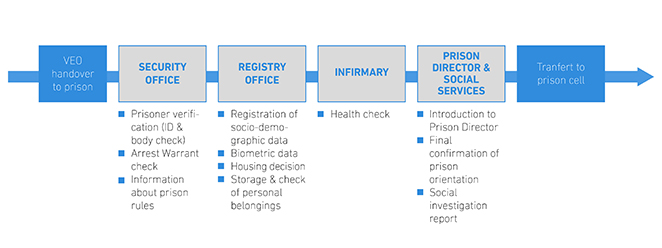

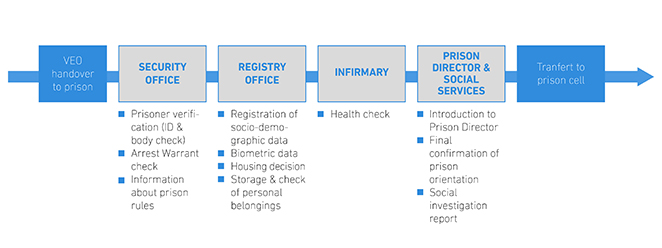

Despite the specific individual profile and background, the intake process of new inmates is relatively similar across Malian prisons. An overall evaluation is conducted by key prison staff through a combination of their professional assessment and an analysis of the charge and the case file. Figure 1 provides an overview of the intake and risk assessment procedure at the Maison Central d’Arrêt in Bamako, and exemplifies the current standard intake process. New inmates are usually transferred to the prison by the Malian police, with a warrant of arrest detailing some basic demographic information (name, date of birth and region) and the charge or sentence of the individual. First, the prisoner is brought to the security office, where he or she is informed of the prison’s rules and procedures, and is assigned to a prison cell. Prison guards also immediately perform a physical security check to ensure that the newly arrived inmate does not carry any weapons or other prohibited items. Then, the administration office, so-called Bureau aux fichiers, creates a file on the prisoner and registers his/her demographic data, biometric data, and fingerprints. The personal belongings of the inmate (including for example a cell phone, identification documents and money) are taken and registered in the prison registry. Next, the inmate undergoes a medical check by the doctor or nurse. Depending on availability, the inmate meets with a social worker who conducts a general interview focused on the prisoner’s background, family history, the motivations for their alleged criminal offence and produces a social investigation report. The prisoner’s file consists of all documents and information related to the inmate during his/her detention, including the warrant of arrest, as well as personal, health, and social-related data. The file can be updated and extended with additional information by the prison personnel having regular contact with the inmates during their detention, especially for what concerns relevant security, administrative and health-related information. Finally, the inmate also meets with the prison director before being brought to the cell.

Figure 1 - Intake process in Malian prisons

With the aim to improve VEOs intake process and risk assessment procedure within the Malian prison system, in 2018-2019 UNICRI and ICCT developed a Risk Assessment Tool to determine the level of radicalization leading to violence and trained prison staff on the use of the tool. Through the use of the tool, prison staff develop a comprehensive assessment of the situation and can suggest priority interventions. At the time of writing, a number of risk assessments have been performed with incoming VEOs in Bamako and Koulikoro prisons. Over time, the risk assessment process should be applied to all VEO inmates thus allowing for a standardized approach and paving the way for the development of tailored rehabilitation and reintegration measures.

VEO’s housing

VEOs5 in prison are classified as high-risk population and housed in two correctional institutions: at the Maison Centrale d’Arrêt in Bamako and in Koulikoro prison, approximately 60 km North-East of Bamako. The number of inmates housed at Bamako’s prison has been growing in the past years and a similar trend is found in the number of incarcerated VEOs: from approximately 62 in 2016, the number of terrorist offenders increased to sharply 270 in early 2020. Among them, only 2 have been sentenced (3%) by the time of writing, while the large majority is in pre-trial detention. Koulikoro’s prison housed 174 inmates as of February 2020, including 49 VEOs, of which ten have been sentenced (20%). With an official capacity of 200, this prison is currently below capacity but, as it is used as a “transit prison” for inmates coming from different regions over the country, the number can vary quickly and greatly, making the overall management challenging.

In Bamako two designated units have been established for the VEO population, generally referred to as the "jihadist block" and the "rebels” quarter: placement is generally determined by the type of group the inmate is (allegedly) affiliated with. The “jihadist block” consists of several cells and a courtyard. Inmates in this unit usually spend their day in the courtyard, while during the night are housed in their respective cells. The courtyard is used for daily activities such as prayer, socialising with other detainees, or for inmates generally biding their time. In Koulikoro, the prison consists of one large cell where VEOs are mixed with the general prison population. They do not have access to the courtyard, and daily activities occur in the cell. Koulikoro prison is currently under reconstruction to extend the overall size of the prison and number of cells. In both prisons, VEOs have access to a doctor or nurse and, if need be, can be hospitalised in the infirmary within the correctional facility.

2. Trajectories of violence of the VEOs inmate population in Mali

According to the data collected through field missions, the VEO population in Malian prisons is estimated to be around 319 VEOs at the time of writing, with numbers changing rapidly. The unpredictability of the numerical trends along with a heterogeneity of actors and approaches involved in the arrest phase make it difficult to elaborate a comprehensive overview of the background of the VEO population currently managed by the Malian prison system. However, the analysis provided below partially contributes to fill this gap, capitalizing on primary data collected through in-depth interviews with 30 VEOs, held at Bamako Maison Centrale d’Arret between 2016 and 2019. Because of unbridgeable limitations, including security concerns and language barriers, the sample of respondents could not be selected randomly. Hence, the analysis elaborated below is not meant to allow for a generalization of VEO profiles in Mali but is rather aimed at sharing some valuable findings in order to contribute to an improved development of tailored and efficient rehabilitation and reintegration measures for VEOs in the country.

Socio-demographic overview

The 30 participants were almost all in pre-trial detention at the moment of the interview, with only one being sentenced to imprisonment, and they were mainly housed in the so-called “jihadists block”. The age of the interviewees ranged from 18 to 64 years old, with almost half (40%) being between 26 and 35 years old, and one third between 16 and 25 years old. The fact that 70% of the interviewees were 35 years old or younger at the moment in which they (allegedly) committed a terrorist offence is in line with the general trends identified by criminology, according to which involvement in criminal activities usually occurs before the age of 30.6

Almost all the participants were Malian citizens, with only one having a different nationality. The participants were mainly (80%) from the north of the country and, in particular, coming from the regions of Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal, namely the areas most affected by terrorism in the aftermath of the 2012 coup d’état. In line with the geographical origin, the ethnic affiliation of the respondents mirrors the spectrum of the groups living in the north of Mali, with more than two thirds of the interviewees declaring to be Arab (37%) or Tuareg/Tamashek (37%). Most recent data collected in 2019-2020 concerning 22 newly incarcerated VEOs show a shift in the place of origin, with more than half coming from central Mali. This reflects how armed violence is progressively affecting new areas, especially in the regions of Mopti and Ségou.

Out of 30 interviewees, 20 were married at the time of the interview and half had children. For what concerns the profession, almost all the respondents declared a certain involvement in farming activities and/or in trade, thus mirroring the most common occupations in a region where wealth and power depend on the transport of goods rather than on the possession of land.7 One participant self-reported his occupation as a scholar of the Quran, while another declared to be a marabout. For what concerns the level of education, almost half of the respondents (48%) had received no formal education, although all appear to have received at least some form of informal education, such as, for example, Arabic lessons in the bush. Half of the interviewees declared to have experienced formal education, ranging from 1 up to 12 years, with one respondent specifically reporting having been educated at a madrassa. The entire sample declared to be Muslim, in line with the religious composition of the country, in which more than 90% of the population is Muslim.8

Participation in violent extremism

Approaching the issue of violent extremism, its consequences for the country and individual forms of participation in and support towards armed and violent groups represents a complex and sensitive topic. Part of the challenges linked to this effort are strictly related to the difficulties in identifying a comprehensive and universally accepted definition of terrorism.9 Second, many different violent extremist and armed groups have been proliferating in the region in the past years, including local insurgents fighting for territorial control as well as regional (i.e. Katibat Macina) and global (i.e. Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and n Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin) terrorist organizations: the rapid shift in alliances among these groups as well as the establishment of additional fighting forces makes it even more difficult to clearly define affiliation. Finally, talking about individual involvement in forms of violent extremism entails various barriers for the interviewees, ranging from fear of legal implications to social desirability.

Being aware of the limitations described above, the following paragraphs provide an analysis of several aspects connected to engagement into violent extremism, ranging from affiliation to reasons for participation. In terms of groups’ membership, approximately half of the respondents declared to have been part of an insurgent/secessionist organization, while almost one third made reference to a terrorist group. Indeed, it is worthy to underline that many respondents approached the topic of affiliation in a vague and contradictory manner, such as mentioning different groups during the interview or denying participation in any form of violence. Crucial historical events occurring in the region were mentioned, stressing their influence and impact on individual trajectories of violence, and acting as what Crenshaw would define as preconditions, “factors that set the stage for terrorism over the long run.”10 In particular, the fall of the Gadaffi regime was referred to in connection with an increased availability of weapons in the region and a significant return of fighters from Libya to Mali. With reference to reasons for engagement, while interviewees were reluctant to talk about personal motivations to join violent organizations, it was possible to approach this topic by reflecting more in general about the reasons that motivate people’s support towards these actors. Among the factors acknowledged during the interviews, several elements have been identified more frequently, namely lack of options, feelings of injustice, economic opportunities, and ideological beliefs.

Self-protection

Lack of other available options was mentioned several times by the interviewees as a reason for engagement into violence. Such a motivation included various interlinked aspects, such as the need to support a group for self-protection and/or to protect families and properties in a scenario characterized by an increasing level of instability and insecurity. Engagement for survival purposes was mentioned by almost half of the sample (14), including those that mentioned membership as having a strategy to ensure protection towards other actors present in the area and perceived as more violent. Some respondents also related the adoption of self-protection mechanisms to unstable or weak governmental presence at the local level.

Feelings of injustice and frustrations

Grievances against the institutions and inter-ethnic cleavages represented the most recurrent factor mentioned by the interviewees in leading to engagement into violence. Interviewees often referred to experiences of injustice, frustrations and neglect as a motivation to join armed groups. Such a category includes very different elements. For some respondents the nature of their grievances was mainly resulting from forms of ethnic discrimination: according to one participant, Fulani, Tuareg and Arabs living in the north of the country are by default seen as terrorists. Many respondents claimed that violent extremist groups are particularly effective in exploiting ethnic tensions and approximately one third of the participants mentioned that support towards violent (extremist) groups can act as a way to overcome the discrimination due to the ethnic affiliation, as a strategy to seek justice. Others denounced a certain level of discretion by the security forces, including foreign counter-terrorism troops, in the performance of the arrests. One respondent even mentioned that this dynamic is a reason for supporting violence after release. On a broader level, several respondents identified the source of grievances with a general feeling of neglect by the authorities and institutions, manifesting itself with limited or non-existent access to basic services, such as health care, food, water and justice. Four respondents acknowledged the efficiency of violent groups present in their regions of origin in the provision of these services. Finally, slightly more than half of the sample (57%) identified the lack of political representation as a cleavage and, in such a dynamic, engagement in violent (extremist) groups was portrayed as a tool to gain political control and power. This holds particularly true for involvement in secessionist movements claiming for the independence of the north of Mali.

Economic opportunities

Almost two thirds of the respondents (57%) referred to economic opportunities as a reason for joining. Such a motivation was mentioned by some of the interviewees in connection to a basic survival need, identifying membership as a strategy to safeguard an existing business or as a mechanism to obtain an occupation. Some interviewees reported an expansion in the trade opportunities for what concerns illicit trafficking (especially in weapons and drugs). The possibility of getting a job was referred to not only as a mean to gain financial resources but also as a way to have a clear role and purpose in life. These findings are partially in line with recent research indicating the revenues and financial benefits provided for as a result of membership that are of particular interest in a context of economic fragility: UNDP reports employment as being the reason for joining a violent extremist group in the African content for 13% of young interviewees.

Ideological beliefs

Participants were generally reluctant to talk about beliefs, ideologies and religion. Less than 15% of the interviewees mentioned ideology or extreme religious beliefs as a reason to engage into violence. This finding is in line with various authors claiming that religion and ideology play a less important role in radicalization towards violent extremism than expected11 and with the fact that, generally, violent extremists do not have a particularly extensive religious knowledge or training.12 One respondent claimed that the perception that religion cannot be granted a key role in politics because of various internal and external pressures and forms of opposition can function as a justification for engagement. A widespread sense of threat and discrimination towards religion has also been detected by UNDP across the African continent and has been identified as a serious source for “future risk with regard to the potential for violent extremism to expand further.”13

Despite different backgrounds, diverse experiences and various push and pull factors mentioned in the interviews, there are some dominant elements that appear to be more recurrent among what the participants identified as reasons for engagement. Many of these elements, such as the survival motif, the economic opportunities and the sense of being a victim of injustices, are strictly connected with structural conditions, which require further actions to gain territorial control over the north in order to provide local communities with security, justice and access to services. In addition, stronger initiatives are required to (re)establish a national sense of belonging, to overcome (perceived) discrimination, to enhance mutual trust among different social actors and to provide all the segments of the population with adequate access to the political discourse and dimension. While many of these activities should occur outside the carceral domain, the prison system can play a significant role in contributing to the main priorities and challenges that Mali is facing.

3. Main challenges for the prison administration in the management of the VEOs population

The main challenges faced by the prison administration in the management of the VEO population relate to a lack of resources affecting different actors and sectors. Overall, the Malian prison system suffers from a significant overcrowding rate, coupled with a general lack of personnel, as well as poor health, safety and security conditions and infrastructures. Additionally, the prison system generally struggles with administrative management and recordkeeping along with the lack of a dedicated ombudsman to receive prisoners’ requests or complaints.

This issue of limited resources and capacity translate into different outcomes depending on the prison. In Koulikoro, the prison consists of one large cell where VEOs are mixed with the general prison population, increasing the risk that they might radicalise other inmates. Indeed, radicalisation in prison settings has been identified as a specific issue of concern,14 considering the proximity and potential vulnerability of some inmates, especially the youngest, facing radical charismatic preachers.15 In Bamako, while VEOs inmates are separated from other offender types, the estimated congestion rate of 615% results in a higher need for strict security measures. In Koulikoro’s prison, an additional challenge comes with the function of a “transit” detention centre resulting in potential rapid and great change in the number and profile of inmates housed, which makes the overall management of the prison and the implementation of rehabilitation and reintegration activities challenging. Such conditions result in the implementation of very limited - both in terms of number and nature - rehabilitation and reintegration activities occurring in Malian prisons, none of which are applicable to violent extremist offenders. Due to limited resources and capacities in terms of security and surveillance, VEOs are not allowed time outside their unit or cell to participate in any of the other activities offered within the prison environment, such as access to the library or the place of worship. Similarly, VEOs cannot participate in the activities offered in the prisons, including attending courses in a tailoring or mechanical workshop, vocational training activities, nor working on a plot of agricultural land or in the prison kitchen. At the moment, only a very small fraction of inmates has access to those activities, also in light of the limited availability in terms of spaces and the infrastructural restrictions. All inmates interviewed in Bamako reported following a very similar routine composed by a few basic activities (sleeping, waking up, eating, praying, washing and, sometimes, reading16 or walking) and declared a certain level of malaise due to the lack of opportunities, training and occupations. Most inmates indicated that they would like to have the opportunity to work and have access to certain activities, in particular vocational skills training.

"All days are the same in prison" ( Tous les jours sont les mêmes en prison)17

The lack of security and surveillance resources and capacities could be partly addressed through the implementation of an advanced risk assessment procedure, which should concern all the inmates, especially if accused of terrorist offences, upon arrival at the prison. Such a procedure consists in assessing the degree of radicalisation in order to determine the potential risks they pose to fellow prisoners, to prison personnel and to society at large, and thus determining appropriate treatment in prison, related to low-, medium- or high-risk categorisation, including providing a starting point for a targeted rehabilitation and reintegration intervention strategy. Risk assessment should be an underlying activity throughout the detention period, and release decisions should also be critically based on a determination of the risk a given individual would pose on re-entering society. However, the initial risk assessment of VEOs at arrival in prison in Mali is somehow skewed by a general lack of information. Indeed, inmates accused of terrorist offences are generally arrested by national and international armed forces in north and central Mali and then transferred to the capital city, where they usually spend some time at Gendarmerie Camp One for further questioning, as well as for categorizing and determining whether to house them in Bamako or Koulikoro Central Prison. Various actors are involved in the different steps from the arrest to imprisonment, thus weakening the data collection process. People accused of terrorism are usually brought in prison with limited data and information about their arrest and charges against them, thus negatively affecting the ability of the prison staff to perform a full-fledged risk assessment.

Another management issue derives from the high number of pre-trial detentions, estimated to represent 60 to 90% of the overall prison population, with similar numbers for the VEO population (97% in Bamako and 80% in Koulikoro as per our estimates). This factor might lead to an increased risk of radicalisation among the detainees charged but not yet sentenced of terrorism (and who might prove innocent) by increasing exposure to recruiters and strengthening a sense of unfair treatment and discrimination. In terms of rehabilitation and reintegration, this results in a situation where less than half of the overall population, and only 3 to 20% of the VEO population, may have access to such R&R interventions.

Another important factor limiting the rehabilitation and reintegration of VEOs in prison relates to the fact that many of the inmates accused of/sentenced for terrorism are incarcerated far away from their family, who are generally unable to visit. Indeed, all VEOs are housed in Bamako and Koulikoro prisons, both situated in the southern part of the country, while many of detainees come from north or central Mali. Despite the long and challenging route for families to reach Bamako and Koulikoro, another difficulty is related to the fact that family visits are generally limited to one day a week: families are then required to remain in the south for several weeks to get to see the inmate more than once. These factors lead to a very reduced number of visits, as reported by the interviewees. This aspect is crucial as families, peers and communities play a fundamental role in the rehabilitation process and their support is essential both during the detention, to provide additional food and services, as well as for the re-entry phase to avoid stigmatisation and prevent recidivism. Linked to this geographical issue is the language barrier, since most of the VEOs speak Arabic or Tamashek, while the languages mostly used in Bamako and Koulikoro are Bambara and French. This might have an impact on social interactions and might limit the possibility for inmates to participate in activities provided in a language they do not master.

"I don't know the others and I don't understand them because they speak other languages like Arabic and Bambara" (Je ne connais pas les autres et je ne les comprends pas parce qu'ils parlent d'autres langues comme l'Arabe et le Bambara)18

Besides the practical aspects detailed above, some behavioural factors must also be taken into account. First, the most radicalized inmates might reject the R&R activities offered by the prison administration, either by simple lack of interest, or as a signal of rejection towards the administration and, more generally, the authorities and institutions, in line with the grievances described above. Second, the development of R&R activities limited to the VEO population might produce a negative effect on the relationships among inmates, arising from a sense of discrimination amid the rest of the prison population, and thus negatively affecting the status of VEOs, who might already suffer from stigmatization within the prison environment. These factors should also be taken into account when developing R&R programmes and interventions in prison.

Finally, in the previous analysis of the factors that play a role in driving extremism in Mali, some elements have been identified as most common and recurrent. Understanding of local and context-specific drivers is essential to effectively prevent and counter violent extremism as well as to successfully identify the main elements that should be at the centre of a comprehensive rehabilitation and reintegration effort. From the primary data collected by UNICRI and ICCT, besides the survival motif, longstanding grievances and frustrations as well as the availability of economic opportunities play a key role in the engagement into violence. Furthermore, ideology also plays a minor role according to the respondents. Despite the great value of the data gathered so far, further efforts should be channelled into developing a more thorough understating of the drivers and trajectories of violence among the VEO population in prison in Mali.

4. Way forward in terms of tailored R&R initiatives for the VEOs population in Mali

Episodes of violence have progressively increased in the Sahel region, going hand in hand with an increased number of prisoners accused of or sentenced for terrorism-related offences. Prisons can function as a unique environment in which inmates can disengage from violence as a result of a comprehensive, tailored and resilient rehabilitation and reintegration strategy. Mali has already undertaken various steps to prevent and counter violent extremism, including the elaboration of a national strategy and an action plan to operationalize it. The Malian prison system has also taken active part in the efforts to apply the national strategy at the penitentiary level with the support of various international actors, such as MINUSMA/JCS, UNODC, UNICRI and ICCT. However, some challenges are still to be addressed, as outlined in the previous sections. The lack of a comprehensive VEOs rehabilitation and reintegration plan should be overcome with the active engagement of the national prison administration and through the elaboration of evidence-based and context-specific measures. As claimed by many experts in this field, the design of R&R initiatives should not follow the “one-size fits all” approach but should rather be tailored to local conditions, culture, legal traditions of the state, and in line with national and international laws and regulations.19 Thus, the prison administration plays a crucial role in this regard given its privileged position when it comes to the identification of main gaps, existing risks, and priority needs. The elaboration of comprehensive, tailored and resilient rehabilitation and reintegration initiatives in Mali requires the leadership and ownership of the DNAPES.

The design of R&R measures should be anchored to empirical results and should constantly rely on action-oriented research and appropriate methodologies which could include building on successful examples of rehabilitation and reintegration measures in Mali concerning the non-VEO population as well as the lessons learned by the neighbouring countries. In addition, research and assessment could help with finding realistic solutions within the existing limitations in terms of infrastructures, lack of personnel, and overcrowding: rehabilitation and reintegration measures can take various forms, such as education training (from basic literacy to more advanced skills), vocational training - either manual (such as woodwork, metalwork, agriculture, bricklaying, cooking, sewing skills, etc.) or intellectual (computer, accounting, entrepreneurial skills, etc.) - psychological counselling and other activities that could be adapted according to the environment. Evidence shows that engagement in vocational training and capacity-building initiatives positively contributes to reducing the drivers that lead to engagement in terrorism and increases the possibilities of finding employment after release, further limiting the recidivism risks and improving security for society at large, as confirmed also by some interviewees, of which one declared that being engaged in some activities would help inmates recover and overcome mental and physical frustrations.

In addition, before designing and implementing R&R initiatives, it is important to define clear objectives, identify clear roles and actors for each phase and clarify the respective responsibilities. All relevant stakeholders shall be engaged, from families to international and civil society organizations, religious leaders, psychologists as well as actors involved in the arrest-to-imprisonment process. Family members can be strong influencers in VEO rehabilitation and their engagement is indeed a way to create ''cognitive openings''20 for disengagement and/or de-radicalization. Given the existing challenges portrayed above, a stronger involvement of the families for VEOs could pass through a revised procedure for family visits, allowing for family members coming from far away to receive authorization to visit for several consequential days in order to reduce the impact of the trip. In addition, the already existing cooperation between international and civil society organizations could be expanded and strengthened within the framework of an R&R plan. One third of the participants interviewed expressly mentioned, for instance, their appreciation towards the regular International Red Cross (ICRC) visits. The involvement of diverse stakeholders in the design and implementation of rehabilitation and reintegration measures requires mutual trust and a structure for facilitating cooperation and information-sharing: creating a stable network for enhanced dialogue, sharing experiences and lessons learned would allow for the development of a more thorough R&R plan, based on a much broader set of information concerning the inmate and his/her trajectory of violence.

“It's nice to have a visit on a regular basis because it creates a stable relationship" (Il est agréable d'avoir une visite sur une base régulière parce que cela crée une relation stable)21

Enhanced knowledge on the VEOs life-history and trajectories of violence would help in designing tailored R&R measures within the prison settings as well as in the outside society. The initial findings presented in this report suggest that addressing the sources of (perceived) injustices and cleavages, would have a significant impact on limiting the avenues for radicalization. Given the general sense of hopelessness detected in the interviewees, working on enhancing trust among different communities as well as between the population and the institutions would also be crucial in addressing the current fragile situation in Mali. In light of the percentage of the prison population in pre-trial detention, the strengthening of the judicial process could also help address the feeling of being a victim of an injustice: to use the words of one interviewee, “keeping the innocents in prison awaiting trial increases tensions in society.” A comprehensive action to enhance VEOs rehabilitation and reintegration should thus also advocate for an improved criminal justice system, more capable and accountable in providing effective responses throughout all the different phases of the criminal justice process. The research presented in this article regarding the reasons for engagement into violent extremism does not claim to be exhaustive but calls, on the contrary, on the need to expand and enhance the understanding of the relevant pull and push factors. Although conducting research in the prison environment implies several challenges, the resulting improved understanding of the phenomenon of violent extremism is crucial for the development of a solid R&R programme: an assessment of the “situation and the underlying social dynamics responsible for social change” would guide the development of tailored policies promoting targeted strategies and solutions.22

Finally, a proper R&R programme should be aligned to the contextual framework and, in the case of Mali, shall complement the on-going implementation of the Agreement on Peace and Reconciliation in Mali, which provides for the integration of former combatants into the security services, as well as the reintegration of them into their communities through the disarmament, demobilization, reintegration and integration programme.23

All of the above elements and recommendations could contribute to the design of a tailored, comprehensive and resilient rehabilitation and reintegration plan for the VEO population in Mali, which represents a crucial component of the country’s efforts in the fight against violent extremism. As claimed by one of the interviewees, former offenders could serve as powerful allies in the fight against violent extremism and could be crucial in the dissemination of targeted peaceful messages across the country.

Endnotes

1All 30 interviewees were selected by prison staff but participated in the interviews voluntarily: a social worker informed the inmates one day before the arrival of the research team, briefly presenting the purpose of the research and the voluntary nature of participation. A research team consisting of two researchers interviewed the 30 inmates. The interviews were not allowed to be audio-recorded but written notes were taken and transcribed immediately after each interview. In general, the interviews took 45-90 minutes each.

2See:

https://www.un.org/ruleoflaw/files/Socioeconomic%20impact%20of%20PTD_Sept%2010%202010_Final.pdf;

http://maliactu.info/societe/la-maison-centrale-darret-mca-de-bamako-un-enjeu-securitaire-qui-ne-reflete-pas-les-conditions-de-vie-et-de-travail-des-surveillants-de-prison;

https://www.prsf.fr/pays-d-intervention/mali

3The United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (https://minusma.unmissions.org/en)

4International Committee of the Red Cross (https://www.icrc.org/en/where-we-work/africa/mali)

5Throughout this publication the term VEOs is used to refer to inmates both arrested as well as sentenced for terrorism-related offenses.

6Jeffrey Todd Ulmer and Darrell J. Steffensmeier, ‘The age and crime relationship: Social variation, social explanations”, The nurture versus biosocial debate in criminology: On the origins of criminal behavior and criminality, SAGE Publications, 2014, pp. 377-396.

7Luca Raineri and Francesco Strazzari, ‘State, Secession, and Jihad: The Micropolitical Economy of Conflict in Northern Mali’, African Security, 8:249–271 (2015), p. 250

8Houssain Kettani, ‘Muslim population in Africa: 1950-2020’, International Journal of Environmental Science and Development, 1:2 (2010), p. 137

9Alex Schmid, ‘Terrorism-the definitional problem’, Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 36 (2004), p. 395

10Martha Crenshaw, ‘The Causes of Terrorism’, Comparative Politics, 13:4 (Jul., 1981), p. 381.

11See Anne Aly and Jason-Leigh Striegher, ‘Examining the role of religion in radicalization to violent Islamist extremism’, Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 35:12 (2012), pp. 849-862.

12Lisa Schirch, ed., The ecology of violent extremism: Perspectives on peacebuilding and human security, Rowman & Littlefield, 2018, p.43.

13UNDP, Journey To Extremism In Africa: Drivers, Incentives and The Tipping Point For Recruitment, 2017, p. 48

14Silke (Ed.), Prisons, Terrorism and Extremism: Critical Issues in Management, Radicalisation and Reform (2014)

15Council of Europe (2016). Handbook for Prison and Probation Services Regarding Radicalisation and Violent Extremism. https://rm.coe.int/16806f9aa9.

16Inmates can request books (generally in French) mainly offered by the church

17VEO inmate interviewed in Bamako’s prison in December 2016

18VEO inmate interviewed in Bamako’s prison in December 2016.

19UNICRI, Strengthening efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism: Good practices and lessons learned for a comprehensive approach to rehabilitation and reintegration of VEOs, 2018, p. 16.

20GCTF, The Role of Families in Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism: Strategic Recommendations and Programming Options.

21VEO inmate interviewed in Bamako’s prison in December 2016.

22Veldhuis, T. M. and Kessels, E. J. Thinking before Leaping: The Need for More and Structural Data Analysis in Detention and Rehabilitation of Extremist Offenders. The Hague, The Netherlands: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2013.

23https://minusma.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/s_2020_223_e.pdf

Introduction

In his remarks to the High-level Meeting on Mali and the Sahel held on the margins of the General Debate of the 74th session of the UN General Assembly, the Secretary General António Guterres acknowledged the increasing threat posed by the rise of violence in the Sahel and its spreading towards the Gulf of Guinea. He also warned about terrorist groups exploiting local conflicts and acting as defenders of communities to enhance their popularity and local support. As a matter of fact, countries in the Sahel region have been experiencing a significant increase in the level of violence, resulting in severe consequences for the population. According to Mohamed Ibn Chambas, UN Special Representative and Head of the United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel (UNOWAS), the casualties caused by terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, have increased five-fold since 2016. The fragile circumstances and the deteriorating security situation have also pushed many people to flee their homes, with more than one million refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) sheltered in the central Sahel.

As the countries in the Sahel region face increasing security threats resulting from terrorism, organized crime and inter-community tensions, the pressure on the prison systems escalates. Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Mali and Mauritania present the highest prison overcrowding rates in the world, ranging from 120% to 232%. Within this framework, a specific threat is represented by the risks of radicalization and/or recruitment taking place in the prison settings in light of the increasing number of suspected violent extremists within both the judicial and correctional systems.

Prisons, with their peculiar characteristics, certainly represent an environment where inmates are more vulnerable as a result of the restrictions of freedom, the loss of means of subsistence, personal effects and housing, the loss of important personal relationships and the deterioration of social and family ties. All these factors may increase the chances of inmates becoming more easily attracted by the advantages of taking part in a radical group while in detention. On the other hand, prisons can play a multi-faceted role in identifying, assessing and countering radicalization and recruitment. Such a unique environment represents an opportunity for the implementation of tailored rehabilitation activities, including targeted rehabilitative measures, capacity-building initiatives and awareness raising opportunities. Under certain circumstances and within the framework of tailored initiatives, incarceration may thus reduce the risk and instead mark the beginning of a disengagement process. In this regard, the design and development of effective rehabilitation and reintegration programs can prevent further radicalization and help deradicalize inmates convicted of terrorism-related offences.

The current article is aimed at assessing the main challenges and opportunities for the development and implementation of targeted rehabilitation and reintegration (R&R) measures for the violent extremist offender (VEO) population in detention in Mali. The first part will provide an overview of the Malian prison system, while the second will focus on the trajectories of violence of the VEO population in Mali. The third section will elaborate on the main challenges faced by the prison administration in the management of suspected/convicted violent extremist offenders, including the development of rehabilitation and reintegration measures. Finally, the conclusion will portray some alternatives in terms of future tailored R&R initiatives for the VEOs population in Mali.

Methodology

In the context of a series of initiatives aimed at countering violent extremism in prisons and fostering community resilience against violent extremism in Mali, the United Nationals Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI), together with the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), have developed and implemented a set of activities over the past four years both within as well as outside the prison settings. This publication is built on this experience and is based on the analysis of existing literature on the region and on the radicalisation process, combined with data gathered during field missions organized by UNICRI and ICCT. Primary data were collected through fieldnotes, as well as unstructured interviews with local, national and international actors, and thirty semi-structured interviews with inmates accused of/ convicted for terrorism-related offences. The semi-structured interviews 1were conducted between 2016 and 2019 in Bamako’s central prison, to enhance the understanding of the detainees’ background and their reasons for engagement with terrorist groups. Finally, supplementary data were gathered on 22 additional VEOs in Bamako Prison in 2019.

1. Overview of the prison system in Mali

Within the Ministry of Justice, the Malian prison administration is directed and managed by the Direction National de l'Administration Pénitentiaire et de l’Education Surveillée (DNAPES), which serves the twofold purpose of custody and reintegration of detainees. The country counts 59 detention centers, including some agricultural and specialized establishments, of which 14 have been destroyed by the conflict in 2013. A new and capacious prison is under construction in the town of Kenieroba, located in the district of Koulikoro, approximately 75 kilometres in the South West of Bamako.

The increased number of arrests due to the criminal activities occurring in the country as well as the impact of the conflict on the detention facilities have been worsening the already critical levels of prison overpopulation. At the end of 2018, the overall prison population exceeded 6,250 inmates. Compared to the official capacity of approximately 3,000 inmates as of 2009, the actual occupancy rate would translate to a general congestion rate of roughly 175%. The number of pre-trial detention cases constitutes a considerable burden for the Malian prison system, with an estimated representation of 60 to 90% of the prison population2 according to various sources. The main prison in Bamako, the Maison Centrale d’Arrêt, has an official capacity of 400 inmates, but, at the end of 2019, it was housing 2,400 people, leading to a congestion rate of 615%. The issue of overpopulation is supposed to be addressed with the new prison of Kenieroba which should have a capacity of 2,500 inmates. At the end of 2019, a group of approximately 440 low-risk offenders were transferred to Kenieroba prison on a trial-basis.

Prison’s actors

Under the authority of the DNAPES, each detention centre is headed by a prison director, or régisseur, in charge of the overall prison management, including both of inmates and staff. Prison personnel is mainly comprised of guards and security officers, managing the prison population on a daily basis and maintaining operational security within the facility. In addition, administrative staff usually composed of fewer individuals are responsible for keeping the general prison administration up to date, registering new inmates and visitors and managing the prison archives. Depending on the available resources, some prisons also employ social workers to focus on prison welfare, as well as rehabilitation and reintegration interventions. In terms of health care, some facilities can count on a doctor or nurse(s) working in the prison, while in other detention centres doctors/nurses visit at regular intervals.

The prison environment also entails connections and links with several external actors. In particular, religious leaders generally visit once a week, for example to conduct the Friday sermon for Muslims and/or to lead Sunday prayer services with Christian inmates. In addition, various international organisations, civil society, or non-governmental organisations (such as MINUSMA3, ICRC4, Prisonnier Sans Frontière, UNICRI, ICCT and Think Peace) support the overall prison management by providing basic services (such as kitchen machinery, healthcare material), education materials or equipment for vocational occupations (such as cloth-making, woodwork, or agriculture); delivering capacity-building activities (e.g. UNICRI and ICCT provided several trainings for security officers, psychologists and religious leaders working in prison to promote the rehabilitation of VEOs in prison); or by conducting research and analysis on needs, gaps and priorities linked to the prison environment. Finally, family members, who generally visit prisoners on pre-approved days and times, may also play a central role in basic services such as provision of additional food as well as relational and emotional support.

Intake process

Despite the specific individual profile and background, the intake process of new inmates is relatively similar across Malian prisons. An overall evaluation is conducted by key prison staff through a combination of their professional assessment and an analysis of the charge and the case file. Figure 1 provides an overview of the intake and risk assessment procedure at the Maison Central d’Arrêt in Bamako, and exemplifies the current standard intake process. New inmates are usually transferred to the prison by the Malian police, with a warrant of arrest detailing some basic demographic information (name, date of birth and region) and the charge or sentence of the individual. First, the prisoner is brought to the security office, where he or she is informed of the prison’s rules and procedures, and is assigned to a prison cell. Prison guards also immediately perform a physical security check to ensure that the newly arrived inmate does not carry any weapons or other prohibited items. Then, the administration office, so-called Bureau aux fichiers, creates a file on the prisoner and registers his/her demographic data, biometric data, and fingerprints. The personal belongings of the inmate (including for example a cell phone, identification documents and money) are taken and registered in the prison registry. Next, the inmate undergoes a medical check by the doctor or nurse. Depending on availability, the inmate meets with a social worker who conducts a general interview focused on the prisoner’s background, family history, the motivations for their alleged criminal offence and produces a social investigation report. The prisoner’s file consists of all documents and information related to the inmate during his/her detention, including the warrant of arrest, as well as personal, health, and social-related data. The file can be updated and extended with additional information by the prison personnel having regular contact with the inmates during their detention, especially for what concerns relevant security, administrative and health-related information. Finally, the inmate also meets with the prison director before being brought to the cell.

Figure 1 - Intake process in Malian prisons

With the aim to improve VEOs intake process and risk assessment procedure within the Malian prison system, in 2018-2019 UNICRI and ICCT developed a Risk Assessment Tool to determine the level of radicalization leading to violence and trained prison staff on the use of the tool. Through the use of the tool, prison staff develop a comprehensive assessment of the situation and can suggest priority interventions. At the time of writing, a number of risk assessments have been performed with incoming VEOs in Bamako and Koulikoro prisons. Over time, the risk assessment process should be applied to all VEO inmates thus allowing for a standardized approach and paving the way for the development of tailored rehabilitation and reintegration measures.

VEO’s housing

VEOs5 in prison are classified as high-risk population and housed in two correctional institutions: at the Maison Centrale d’Arrêt in Bamako and in Koulikoro prison, approximately 60 km North-East of Bamako. The number of inmates housed at Bamako’s prison has been growing in the past years and a similar trend is found in the number of incarcerated VEOs: from approximately 62 in 2016, the number of terrorist offenders increased to sharply 270 in early 2020. Among them, only 2 have been sentenced (3%) by the time of writing, while the large majority is in pre-trial detention. Koulikoro’s prison housed 174 inmates as of February 2020, including 49 VEOs, of which ten have been sentenced (20%). With an official capacity of 200, this prison is currently below capacity but, as it is used as a “transit prison” for inmates coming from different regions over the country, the number can vary quickly and greatly, making the overall management challenging.

In Bamako two designated units have been established for the VEO population, generally referred to as the "jihadist block" and the "rebels” quarter: placement is generally determined by the type of group the inmate is (allegedly) affiliated with. The “jihadist block” consists of several cells and a courtyard. Inmates in this unit usually spend their day in the courtyard, while during the night are housed in their respective cells. The courtyard is used for daily activities such as prayer, socialising with other detainees, or for inmates generally biding their time. In Koulikoro, the prison consists of one large cell where VEOs are mixed with the general prison population. They do not have access to the courtyard, and daily activities occur in the cell. Koulikoro prison is currently under reconstruction to extend the overall size of the prison and number of cells. In both prisons, VEOs have access to a doctor or nurse and, if need be, can be hospitalised in the infirmary within the correctional facility.

2. Trajectories of violence of the VEOs inmate population in Mali

According to the data collected through field missions, the VEO population in Malian prisons is estimated to be around 319 VEOs at the time of writing, with numbers changing rapidly. The unpredictability of the numerical trends along with a heterogeneity of actors and approaches involved in the arrest phase make it difficult to elaborate a comprehensive overview of the background of the VEO population currently managed by the Malian prison system. However, the analysis provided below partially contributes to fill this gap, capitalizing on primary data collected through in-depth interviews with 30 VEOs, held at Bamako Maison Centrale d’Arret between 2016 and 2019. Because of unbridgeable limitations, including security concerns and language barriers, the sample of respondents could not be selected randomly. Hence, the analysis elaborated below is not meant to allow for a generalization of VEO profiles in Mali but is rather aimed at sharing some valuable findings in order to contribute to an improved development of tailored and efficient rehabilitation and reintegration measures for VEOs in the country.

Socio-demographic overview

The 30 participants were almost all in pre-trial detention at the moment of the interview, with only one being sentenced to imprisonment, and they were mainly housed in the so-called “jihadists block”. The age of the interviewees ranged from 18 to 64 years old, with almost half (40%) being between 26 and 35 years old, and one third between 16 and 25 years old. The fact that 70% of the interviewees were 35 years old or younger at the moment in which they (allegedly) committed a terrorist offence is in line with the general trends identified by criminology, according to which involvement in criminal activities usually occurs before the age of 30.6

Almost all the participants were Malian citizens, with only one having a different nationality. The participants were mainly (80%) from the north of the country and, in particular, coming from the regions of Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal, namely the areas most affected by terrorism in the aftermath of the 2012 coup d’état. In line with the geographical origin, the ethnic affiliation of the respondents mirrors the spectrum of the groups living in the north of Mali, with more than two thirds of the interviewees declaring to be Arab (37%) or Tuareg/Tamashek (37%). Most recent data collected in 2019-2020 concerning 22 newly incarcerated VEOs show a shift in the place of origin, with more than half coming from central Mali. This reflects how armed violence is progressively affecting new areas, especially in the regions of Mopti and Ségou.

Out of 30 interviewees, 20 were married at the time of the interview and half had children. For what concerns the profession, almost all the respondents declared a certain involvement in farming activities and/or in trade, thus mirroring the most common occupations in a region where wealth and power depend on the transport of goods rather than on the possession of land.7 One participant self-reported his occupation as a scholar of the Quran, while another declared to be a marabout. For what concerns the level of education, almost half of the respondents (48%) had received no formal education, although all appear to have received at least some form of informal education, such as, for example, Arabic lessons in the bush. Half of the interviewees declared to have experienced formal education, ranging from 1 up to 12 years, with one respondent specifically reporting having been educated at a madrassa. The entire sample declared to be Muslim, in line with the religious composition of the country, in which more than 90% of the population is Muslim.8

Participation in violent extremism

Approaching the issue of violent extremism, its consequences for the country and individual forms of participation in and support towards armed and violent groups represents a complex and sensitive topic. Part of the challenges linked to this effort are strictly related to the difficulties in identifying a comprehensive and universally accepted definition of terrorism.9 Second, many different violent extremist and armed groups have been proliferating in the region in the past years, including local insurgents fighting for territorial control as well as regional (i.e. Katibat Macina) and global (i.e. Islamic State in the Greater Sahara and n Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin) terrorist organizations: the rapid shift in alliances among these groups as well as the establishment of additional fighting forces makes it even more difficult to clearly define affiliation. Finally, talking about individual involvement in forms of violent extremism entails various barriers for the interviewees, ranging from fear of legal implications to social desirability.

Being aware of the limitations described above, the following paragraphs provide an analysis of several aspects connected to engagement into violent extremism, ranging from affiliation to reasons for participation. In terms of groups’ membership, approximately half of the respondents declared to have been part of an insurgent/secessionist organization, while almost one third made reference to a terrorist group. Indeed, it is worthy to underline that many respondents approached the topic of affiliation in a vague and contradictory manner, such as mentioning different groups during the interview or denying participation in any form of violence. Crucial historical events occurring in the region were mentioned, stressing their influence and impact on individual trajectories of violence, and acting as what Crenshaw would define as preconditions, “factors that set the stage for terrorism over the long run.”10 In particular, the fall of the Gadaffi regime was referred to in connection with an increased availability of weapons in the region and a significant return of fighters from Libya to Mali. With reference to reasons for engagement, while interviewees were reluctant to talk about personal motivations to join violent organizations, it was possible to approach this topic by reflecting more in general about the reasons that motivate people’s support towards these actors. Among the factors acknowledged during the interviews, several elements have been identified more frequently, namely lack of options, feelings of injustice, economic opportunities, and ideological beliefs.

Self-protection

Lack of other available options was mentioned several times by the interviewees as a reason for engagement into violence. Such a motivation included various interlinked aspects, such as the need to support a group for self-protection and/or to protect families and properties in a scenario characterized by an increasing level of instability and insecurity. Engagement for survival purposes was mentioned by almost half of the sample (14), including those that mentioned membership as having a strategy to ensure protection towards other actors present in the area and perceived as more violent. Some respondents also related the adoption of self-protection mechanisms to unstable or weak governmental presence at the local level.

Feelings of injustice and frustrations

Grievances against the institutions and inter-ethnic cleavages represented the most recurrent factor mentioned by the interviewees in leading to engagement into violence. Interviewees often referred to experiences of injustice, frustrations and neglect as a motivation to join armed groups. Such a category includes very different elements. For some respondents the nature of their grievances was mainly resulting from forms of ethnic discrimination: according to one participant, Fulani, Tuareg and Arabs living in the north of the country are by default seen as terrorists. Many respondents claimed that violent extremist groups are particularly effective in exploiting ethnic tensions and approximately one third of the participants mentioned that support towards violent (extremist) groups can act as a way to overcome the discrimination due to the ethnic affiliation, as a strategy to seek justice. Others denounced a certain level of discretion by the security forces, including foreign counter-terrorism troops, in the performance of the arrests. One respondent even mentioned that this dynamic is a reason for supporting violence after release. On a broader level, several respondents identified the source of grievances with a general feeling of neglect by the authorities and institutions, manifesting itself with limited or non-existent access to basic services, such as health care, food, water and justice. Four respondents acknowledged the efficiency of violent groups present in their regions of origin in the provision of these services. Finally, slightly more than half of the sample (57%) identified the lack of political representation as a cleavage and, in such a dynamic, engagement in violent (extremist) groups was portrayed as a tool to gain political control and power. This holds particularly true for involvement in secessionist movements claiming for the independence of the north of Mali.

Economic opportunities

Almost two thirds of the respondents (57%) referred to economic opportunities as a reason for joining. Such a motivation was mentioned by some of the interviewees in connection to a basic survival need, identifying membership as a strategy to safeguard an existing business or as a mechanism to obtain an occupation. Some interviewees reported an expansion in the trade opportunities for what concerns illicit trafficking (especially in weapons and drugs). The possibility of getting a job was referred to not only as a mean to gain financial resources but also as a way to have a clear role and purpose in life. These findings are partially in line with recent research indicating the revenues and financial benefits provided for as a result of membership that are of particular interest in a context of economic fragility: UNDP reports employment as being the reason for joining a violent extremist group in the African content for 13% of young interviewees.

Ideological beliefs

Participants were generally reluctant to talk about beliefs, ideologies and religion. Less than 15% of the interviewees mentioned ideology or extreme religious beliefs as a reason to engage into violence. This finding is in line with various authors claiming that religion and ideology play a less important role in radicalization towards violent extremism than expected11 and with the fact that, generally, violent extremists do not have a particularly extensive religious knowledge or training.12 One respondent claimed that the perception that religion cannot be granted a key role in politics because of various internal and external pressures and forms of opposition can function as a justification for engagement. A widespread sense of threat and discrimination towards religion has also been detected by UNDP across the African continent and has been identified as a serious source for “future risk with regard to the potential for violent extremism to expand further.”13

Despite different backgrounds, diverse experiences and various push and pull factors mentioned in the interviews, there are some dominant elements that appear to be more recurrent among what the participants identified as reasons for engagement. Many of these elements, such as the survival motif, the economic opportunities and the sense of being a victim of injustices, are strictly connected with structural conditions, which require further actions to gain territorial control over the north in order to provide local communities with security, justice and access to services. In addition, stronger initiatives are required to (re)establish a national sense of belonging, to overcome (perceived) discrimination, to enhance mutual trust among different social actors and to provide all the segments of the population with adequate access to the political discourse and dimension. While many of these activities should occur outside the carceral domain, the prison system can play a significant role in contributing to the main priorities and challenges that Mali is facing.

3. Main challenges for the prison administration in the management of the VEOs population

The main challenges faced by the prison administration in the management of the VEO population relate to a lack of resources affecting different actors and sectors. Overall, the Malian prison system suffers from a significant overcrowding rate, coupled with a general lack of personnel, as well as poor health, safety and security conditions and infrastructures. Additionally, the prison system generally struggles with administrative management and recordkeeping along with the lack of a dedicated ombudsman to receive prisoners’ requests or complaints.

This issue of limited resources and capacity translate into different outcomes depending on the prison. In Koulikoro, the prison consists of one large cell where VEOs are mixed with the general prison population, increasing the risk that they might radicalise other inmates. Indeed, radicalisation in prison settings has been identified as a specific issue of concern,14 considering the proximity and potential vulnerability of some inmates, especially the youngest, facing radical charismatic preachers.15 In Bamako, while VEOs inmates are separated from other offender types, the estimated congestion rate of 615% results in a higher need for strict security measures. In Koulikoro’s prison, an additional challenge comes with the function of a “transit” detention centre resulting in potential rapid and great change in the number and profile of inmates housed, which makes the overall management of the prison and the implementation of rehabilitation and reintegration activities challenging. Such conditions result in the implementation of very limited - both in terms of number and nature - rehabilitation and reintegration activities occurring in Malian prisons, none of which are applicable to violent extremist offenders. Due to limited resources and capacities in terms of security and surveillance, VEOs are not allowed time outside their unit or cell to participate in any of the other activities offered within the prison environment, such as access to the library or the place of worship. Similarly, VEOs cannot participate in the activities offered in the prisons, including attending courses in a tailoring or mechanical workshop, vocational training activities, nor working on a plot of agricultural land or in the prison kitchen. At the moment, only a very small fraction of inmates has access to those activities, also in light of the limited availability in terms of spaces and the infrastructural restrictions. All inmates interviewed in Bamako reported following a very similar routine composed by a few basic activities (sleeping, waking up, eating, praying, washing and, sometimes, reading16 or walking) and declared a certain level of malaise due to the lack of opportunities, training and occupations. Most inmates indicated that they would like to have the opportunity to work and have access to certain activities, in particular vocational skills training.

"All days are the same in prison" ( Tous les jours sont les mêmes en prison)17

The lack of security and surveillance resources and capacities could be partly addressed through the implementation of an advanced risk assessment procedure, which should concern all the inmates, especially if accused of terrorist offences, upon arrival at the prison. Such a procedure consists in assessing the degree of radicalisation in order to determine the potential risks they pose to fellow prisoners, to prison personnel and to society at large, and thus determining appropriate treatment in prison, related to low-, medium- or high-risk categorisation, including providing a starting point for a targeted rehabilitation and reintegration intervention strategy. Risk assessment should be an underlying activity throughout the detention period, and release decisions should also be critically based on a determination of the risk a given individual would pose on re-entering society. However, the initial risk assessment of VEOs at arrival in prison in Mali is somehow skewed by a general lack of information. Indeed, inmates accused of terrorist offences are generally arrested by national and international armed forces in north and central Mali and then transferred to the capital city, where they usually spend some time at Gendarmerie Camp One for further questioning, as well as for categorizing and determining whether to house them in Bamako or Koulikoro Central Prison. Various actors are involved in the different steps from the arrest to imprisonment, thus weakening the data collection process. People accused of terrorism are usually brought in prison with limited data and information about their arrest and charges against them, thus negatively affecting the ability of the prison staff to perform a full-fledged risk assessment.

Another management issue derives from the high number of pre-trial detentions, estimated to represent 60 to 90% of the overall prison population, with similar numbers for the VEO population (97% in Bamako and 80% in Koulikoro as per our estimates). This factor might lead to an increased risk of radicalisation among the detainees charged but not yet sentenced of terrorism (and who might prove innocent) by increasing exposure to recruiters and strengthening a sense of unfair treatment and discrimination. In terms of rehabilitation and reintegration, this results in a situation where less than half of the overall population, and only 3 to 20% of the VEO population, may have access to such R&R interventions.